Empowering Southeast Asian Youth for Sustainability & Regeneration

On April 19th, 2025, DEEP EnGender proudly launched the Youth-Inclusive Learning Academy (YILA Academy)—a vibrant, virtual initiative designed to empower the next generation of changemakers across Southeast Asia. YILA Academy is more than just a program; it is a movement. It builds on the momentum of our previous youth-led project, Indigenous Rights to Education for Sustainability, which was selected for the Youth Empowerment Fund 2024, supported by Global Youth Mobilization and funded by the European Union.

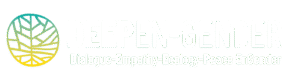

This year, YILA Academy proudly welcomes 21 passionate youth leaders aged 15–18 from Indonesia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, and Timor-Leste. These young voices are united by a shared commitment to sustainability, justice, and collective regeneration. The 2025 cohort represents a rich diversity of backgrounds—rural and conflict-affected areas, urban centers, and international classrooms. Among the participants are artists, environmental defenders, aspiring educators, tech-savvy innovators, and inclusion advocates. Many have overcome barriers such as limited access to education, disability, or social stigma, and now bring with them stories of resilience, creativity, and courage. Despite their different paths, they all share one powerful vision: a future that is sustainable, inclusive, and equitable for all.

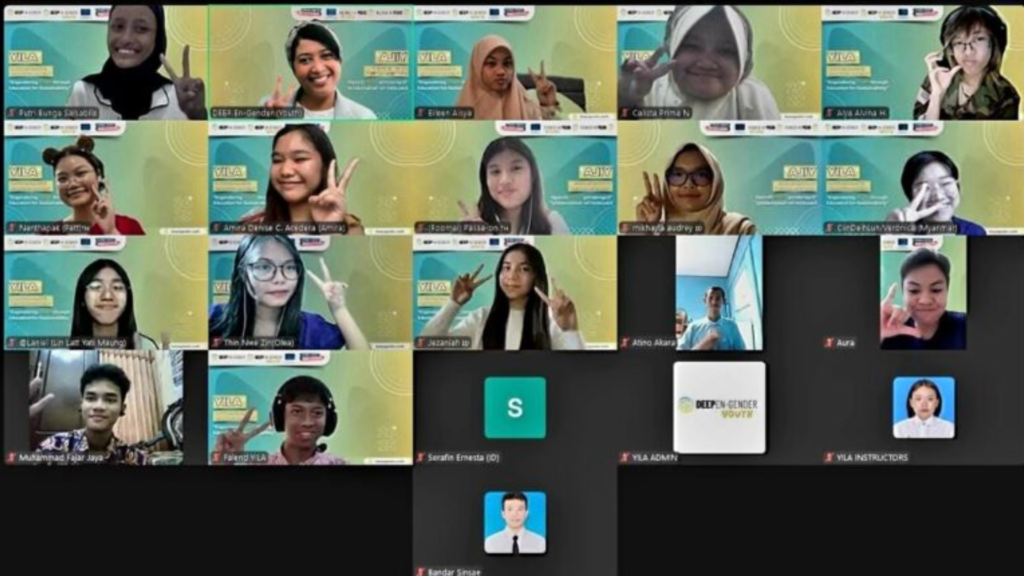

The program was opened with a powerful keynote by Prof. Alberto Gomes, founder of the Global Deep Network. He encouraged participants to become the “lamp”—a Sanskrit term for Deep—that shines a light on the path toward ecological regeneration and a more compassionate world. His remarks set the tone for a journey centered on empathy, awareness, and action.

YILA Academy will run from April 19 to June 14, 2025, consisting of nine weekly sessions held every Saturday. The academy focuses on building key communication skills—storytelling, public speaking, and sustainability advocacy—through interactive workshops, deep reflections, and collaborative discussions. These sessions are designed not only to strengthen participants’ voices, but also to provide a space where ideas are exchanged and collective solutions are nurtured.

The learning journey is led by Dr. Anna Christi Suwardi, Ph.D., a certified educator under the UK Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF) with Fellow (FHEA) status. She is supported by a passionate team of instructors, including Mr. Bandar Sinsae, Ms. Waenarima Waeyama, Ms. Bonyapat Moonrat, and Ms. Phoelina Tiew from Mae Fah Luang University, as well as Mr. Afalendra Fathineyza S. from Samakkhi Wittayakhom School International Program. Together, they guide participants through a transformative process of personal and collective empowerment.

Through YILA Academy, these youth are not only gaining essential skills in communication and leadership, but are also forging bonds across borders and cultures. The academy provides a platform for them to amplify unheard voices, challenge injustice, and work toward systemic change. It is not simply a training program—it is a collaborative journey where young people lead the way in reimagining the future and shaping sustainable solutions grounded in empathy and equity.

Empowering Southeast Asian Youth for Sustainability & Regeneration Read More »